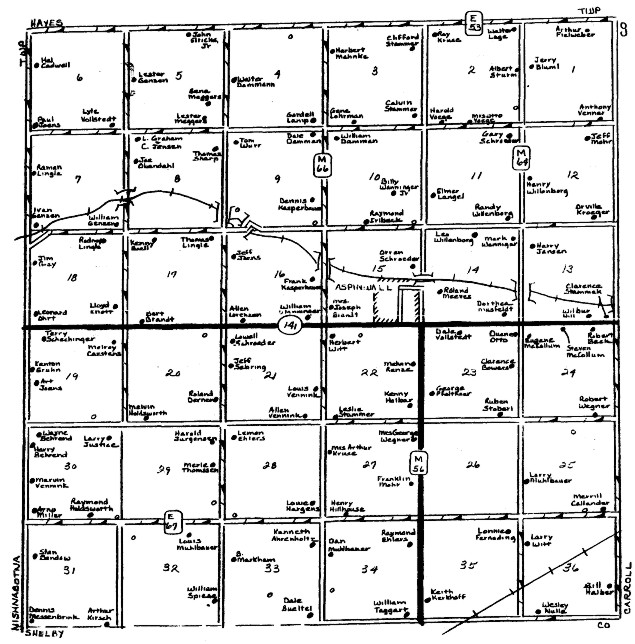

Aspinwall, Iowa -- "I've never had trouble with the rootworm but I think I'll use some treatment this year. I'd hate to lose a whole crop for a few dollars." Billy Wanninger, 30, summed up the thinking of several farmers in this Crawford County area of western Iowa concerning the resistant western corn rootworm threat.

In conversations with farmers north and west of Aspinwall, there were only a few who actually were hurt by the rootworm last year, but most of them don't want to take any chances with this year's crop.

Wanninger feeds 150 head of feeder cattle and raises 2,000 feeder pigs on his 80-acre farm.

Henry Willenborg, Jr., 36, who farms 238 acres, was one who had rootworm trouble last year. "In one 22-acre piece, they cut the yield about 50 bushels per acre and that ground had been beating 100 bushels in yield before that," he said. A continuous-corn advocate, Willenborg figures he can continue with 200 acres of corn this year and combat the rootworm with chemicals.

Howard Saunders, 44, thinks he had root-worm trouble on ground which was in corn for the first time last year. But Saunders is more concerned about cattle prices. "I backed down a year ago and didn't have the livestock I had before. I can tell you there are three of us in a

Continued from page 347

line here who have cut down on cattle," Saunders said.

Despite concern over cattle prices, there were some farmers who reported they made some money on cattle sold during the winter. William Wanninger, 60, father of Billy, said, "I made a little money but I wouldn't like to gamble like that every year. It was the good gain during the winter that did it. Both the commission man and I missed the weight of the animals by about 100 pounds."

Donald Wiese, 37, who has 240 acres of land, also said his cattle put on much more weight during the winter than he expected. He said mild weather let the animals gain well. Wiese said he is cutting down on cattle but stepping up hog production this year. "I'm going into the feed grain program all the way this year, 50 per cent participation. I thought this would be a dry year and then the payments are pretty good this year," he said.

Another factor was the abundance of corn from last year. "I've got a good corn overrun this year, one whole crib left," he said. Thus, his cut in corn production this year won't slow his livestock production.

Wiese and Jerome Irlbeck, 27, another farmer who has stepped up participation in the feed grain program, both are going to raise more soybeans this year as a substitute crop for corn. Irlbeck said he is in the program because he has a good feed grain production base, on which his payments are figured. But his brother Raymond, 24, isn't in the program.

Raymond recently took over a 160-acre farm which had been used intensely for dairy farming, with high amounts of pasture but little corn. Thus, his historic feed grain base is low. "When anyone asks me if I'm in the program, I get mad," Raymond said. "I think they should change the feed grain base every time the tenant changes."

Marvin Hansen, 50, feels the federal feed grain program has changed the character of farming in this area. "This used to be corn, oats, and hay country around here," he said. "Now it's mostly corn and beans. Farmers idle their corn ground, but have done away with oats and shifted to beans," Hansen said.

Many farmers feel the increased production of soybeans will mean a drop in the price of beans by next fall.

Wilbur Anthony, 54, who farms 250 acres alone, said he's noticed other changes in farming. "It used to be that everyone with 160 acres had a hired man," he said, "Now we do the work with four-row planters and other machinery."

ODDS AND ENDS

The threshing ring in my folks' neighborhood in the late 1930s included Charlie

Pfoltner, Herman Schroeder, Frank Meggers, Harry Georgius, Hans Jurgensen,

Mevis Wiese, and Hubert Lamp, all living within a couple of miles north of

Aspinwall. The thresher was provided by Alfred Ehrichs and his son John E.

Lucille (Lamp) Boell

ODDS AND ENDS

It must have been during the winter of 1936 or 1937

when several neighbors helped us butcher. One neighbor saved the blood for

blood pudding. Before removing (scraping) the hair from the hog, the hog was

dipped into a big wooden barrel of hot water. After the hog was cleaned it was

hung up in the corn crib for a few days. Then the meat was cut up on the

kitchen table. We had a smoke house, so fixed our own bacon and ham, and

believe there were times we also fixed our own dried beef. There were times

when the meat was in a brine. The best part was when

we had meat made up into summer sausage.

Mrs. Joan Kriens, Raytown, Missouri

Page 349

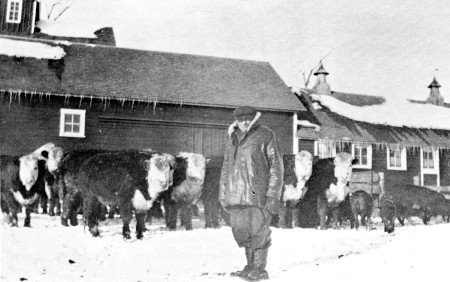

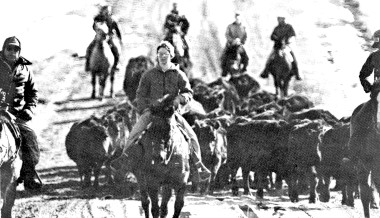

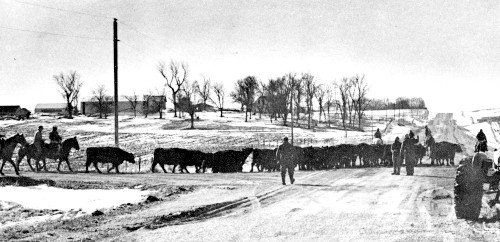

Cattle Drive...1982 Style

A cattle drive, common in the past but not too familiar

today, was held in February, 1982, when cattle were brought home for calving on

the Louis Boell farm north of Aspinwall. The herd had been

gleaning cornstalk ground on the Paul Boell farm during the winter months, and

were being herded home for the upcoming calving season.

Louis and his daughter Brenda were assisted by fellow members of the Rough

Riders Saddle Club; they all agreed the fun was over much too soon. The cattle

knew the way, and with horses in the lead and horses in the rear, there was

only one place for the cattle to go ... home.

Lucille Boell

Page 350

ODDS AND ENDS

My step-father, William H. Schrum had many beautiful

horses. They were golden in color with light or dark manes and tails. Reminds me

of the Palominos now; he also had sorrels. While we were living near Aspinwall,

he sold a matched team for $500.00. Then, I believe in the summer of 1937, we

lost a good many horses to sleeping sickness. The veterinary would come out and

give the horses a shot, but I don't remember much help for the horses. We would

walk some to keep them moving and no help.

Mrs. Joan Kreins, Raytown, Missouri

ODDS AND ENDS

Claus Stammer arrived at his new farm 1 1/2 miles north of Aspinwall in 1879, a

few months before he sent for his wife Catherina and

three sons, who were staying in Clinton. The farm had no house, so they rented

a home 1/2 mile to the east on the south side of the road; the buildings are no

longer there. For the first three years, the closest trading point was at

Westside, where the family took its wheat for grinding and bought groceries and

other supplies.

The farm, like most in the area, had few -- if any -- trees. While coming home

from one of the trading trips to Westside, Catherina

found a pine seedling which she dug and then transplanted on the farm. The tree

grew into one of the tallest on the farm; it was to the east of the original

house and north of the present house. It was struck by lightning at least two

times, and finally had to be cut down in 1979, 100 years after it had been

planted.

Calvin Stammer, Catherina's great grandson

ODDS AND ENDS

Back in 1927, at the age of 21, three of us guys decided to go West and work in

the harvest fields. We went as far as Baker, Montana, and there we found a job

by inquiring at a gas station. We were sent to a farmer named Curtis Shreve,

who hired all of us. We were earning $4 a day in Montana, compared to the $2 a

day wages offered back home. We worked there two months; our meals were

furnished, with breakfast being as large as our dinners and suppers. We worked

in Montana until their rainy season began, at which time we came home and

started picking corn.

Working in Montana was my first experience of running a binder. The land in

that state looks rough, and one wouldn't think there was a place for oats. But

wherever there was a flat area (a plateau or a valley), it would be great for

farming. It was a great experience, even though we didn't make much money.

Paul Boell

ODDS AND ENDS

The arrival of spring meant time to do the butchering

for the yearly supply of meat. We usually butchered three or four hogs, and our

neighbor's daughter, Irene Meggers (now Mrs. Lester Genzen) was asked to come

and help for a week. I don't remember Irene ever being paid; it was just gratus.

Lucille (Lamp) Boell

Page 351

Corn Husking Contests

Husking corn by hand was a necessity in the

pre-machine days, but it was also an art which required dexterity, skill, and

speed. It was only natural that one farmer would want to prove his skills over

another, so contests between corn-huskers were frequently held.

At least one area farmer excelled at the sport. Julius Koester entered contests from 1935 through 1941, often winning county and district meets. In 1938, he won in Carroll County at the contest held at the Frank Hoffmann farm near Westside, where the corn was estimated to be yielding 80 bushels an acre; Julius husked a record 2,036 pounds. Also in 1938, he was the Crawford County Champion, with Leroy Schumann taking second place. Julius then won the district meet, and was therefore eligible for the state husking contest which was held at Ringsted Monday, October 24, 1938.

He was interviewed on radio station WOI, Ames; this was the broadcast: "Julius has competed in four contests held throughout the years in Crawford County. He has placed second or near the top in 1934, 1935, and 1936, and this year placed first at Arcadia. He will give a good account of himself in this state contest.

"The field of national hybrid corn is a good field to pick in. The contest is in charge of businessmen, Farm Bureau members, and County Agent Cloverdale, and is well planned and managed. Wagons are pulled by tractors; husking lands were opened by mechanical pickers.

"We are now at wagon No. 9. Koester -- How do you pronounce that, Koster or Kuster? Koester is stripped to the waist. His right hand is bleeding. Several of these are bad cuts from recent contests. He has now torn off his gloves and is sweating. Koester is throwing 40 ears per minute. A 12-year-old girl is driving the tractor pulling Koester's wagon. Koester is now going faster, throwing 44 ears per minute."

Julius finished the state contest with a second place, husking a net of 2,050 pounds. Accompanying him to the state meet were Gus Koester, Ida Wunder, Hubert Lamp and Eunice Lamp.

He lost out to Earl Justice and Leroy Schumann in the 1939 Crawford County contest, although he finished second in the district meet that year. But in 1941, the last year for the Carroll County contest, Julius returned the champion.

ODDS AND ENDS

There was the time my father, Hubert Lamp, was asked to help move Julius Dammanns

from their home north of Aspinwall to their future

home south of Manning. Moving was done with wagons, with mud as deep as the axles

on the wagons. Dad was to help haul the sows on his wagon, so he left early in

the morning, and on his departing, said, "I don't know when I'll be

home." Moving the sows to the next farm was a one-day ordeal, with a

switch of horses enroute. It took the entire

following day for his return home, which involved switching back to his original team of horses.

Lucille Boell

Page 352

ODDS AND ENDS

Threshing the shocked grain in the summertime was

always a very hard job for the farm men and women, but lots of fun for the

kids. Kids had to carry water and lunch to the fields and gather cobs and wood

for the kitchen stoves to use for cooking and baking. Threshing crews of 15 to

20 men pitched and hauled the grain bundles to the threshing machines. Straw

was stacked by hand.

Food had to be prepared in advance to feed the crew two lunches, dinner and

supper for several days at a time. Bread, pies, cookies and cakes were baked

and meals cooked on wood-burning ranges which produced a lot of heat in the

homes at that time of the year. With no refrigeration, many a trip was made up

and down cellar steps to try to keep the milk and cream cool and to churn the

cream to make butter.

We put our milk and butter products in a wire basket that was lowered into a

cistern with a rope to keep them cool.

Mrs. Alvan (Elaine Schroeder) Hansen

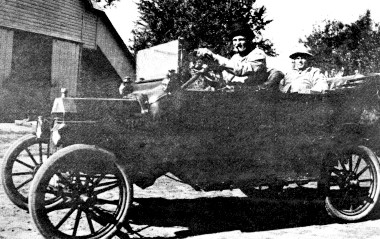

Homesteading in Montana

Henry Guth and John Schilling were among the young men who homesteaded in

central Montana in the early 1900s. Guth filed for his homestead in the fall of

1913 and Schilling filed in the fall of 1914; they returned the following

springs to begin working the land. Schilling's claim for 240 acres from the

U.S. Government was filed September 29, 1919, for a $1.50 fee.

The homesteaders were each permitted five months leave of absence from their land each year, and Henry would use this time to return to Iowa and help on the Guth farm at Aspinwall. Schilling remained at the homesteads, taking care of things there.

Railroad fare one way on the Milwaukee Railroad from Aspinwall to Sumatra, Montana was $20.40. By 1975, the population of Sumatra had dropped to seven, with very little of the once lively town remaining.

Guth owned a team of mules and one or two horses, and Schilling owned one horse. In 1915, the two men purchased a John Deere binder. The dealer wanted $150, but the binder was new and not assembled, and the dealer didn't know how to put it together. He deducted $25 for assembly, and Guth and Schilling borrowed the $125 from the local banker at 12% interest.

Schilling sold his homestead to Sumatra store owners Mr. and Mrs. Walter Sweeney in 1919 for $1,000. Guth's land was later sold for $1,500.

Robert Schilling, his wife Helen and daughter Dianne traveled to Montana in 1975 to visit his father's homestead. The old wagon trails were still clearly visible, and about 1/3 of the posts Schilling dug were still standing straight, with the remaining posts laying where they fell. The one room cabin had long been moved; they found the remains of an old uprooted tree, possibly one of the two trees Schilling had talked of planting in the treeless area. Guth, then 82, and living in Wilsaw, Montana, was the tour guide.

ODDS AND ENDS

I remember farm life by our seemingly annual moves to different farms, and how

much they drained our family. The moves always occurred March 1. It was always

bitterly cold as the wagon with our worldly possessions bumped over frozen ruts

on the dirt roads. I remember having to walk alongside the wagon to keep from

freezing. Sometimes the move from one farm to another involved a considerable

distance, and this, with the lack of proper clothing, made life bitter.

John Babik, Omaha

Page 353

Page 354

Page 355

Medicine and Health Guides

Aspinwall was fortunate to have a physician in town from the beginning of our

existence in 1882 until late 1886. Dr. Gardner was the man who cared for the

sick and delivered the babies during those early years. In the fall of 1886, he

left Aspinwall and began a practice in the town of Manilla, which was just

beginning to form seven miles to the west. Many of Dr. Gardner's former

Aspinwall patients would make that "long journey" to Manilla to be

attended when the need arose.

Aspinwall had a very capable midwife in town in the early 1900s. Mrs. John (Anna) Will assisted in the deliveries of many babies and she usually worked without the assistance of a doctor. The husbands and women friends of the mothers-to-be would lend a hand and do what they could to help.

In those times, having a baby meant at least 10 days in bed for the new mother. This was to allow time for the "female organs to get back in place."

Other old practices and beliefs concerning childbirth were: Never sweep the floor or walk up and down steps after birth.

Never, ever, do any canning while pregnant! The jars will not seal!

Later on, Dr. Carlile and Dr. Smith from Manning would come to the Aspinwall homes to deliver the babies.

Amanda Clausen recalls the time she was assisting while Emma Schilling was delivering one of her children at home. Amanda was instructed by the doctor to give Emma ether. After a while John, the concerned husband, asked Amanda if she wasn't "overdoing it." Emma was pretty well gone and John commented she had never been that way before! Amanda said that was the end of her days as an anesthetist!

Because doctors weren't near at hand, many people in the earlier days had to rely on "home remedies" or "home cures."

For a cold, you were to put "goose grease" on your throat and rub the grease in well. Then you were to wrap a stocking around your neck to keep the medicine "in."

For a cough, you were to cook a syrup of onions and sugar and take a couple spoonfuls. Everyone said this tasted "horrible!"

For a sore throat, you mixed skunk grease and turpentine together and smeared it on the throat. It smelled like turpentine, not skunk!

For boils and open sores, you mixed water and Adopis (ground linseeds) together, put it in a cloth bag and placed it directly on the sore; this drew the poison out.

For earaches, you put warm olive oil in the ear. For toothaches, you applied liquid cloves to the tooth.

Susan Schilling still uses a family remedy that was passed down by her mother, Evelyn Grundmeier. For drawing out infections you mix milk and bread, heat it until almost boiling, place the poultice on a soft rag and apply, as hot as possible, directly to the sore. Wrap the area, and leave it on overnight or at least several hours. This draws out infection, and Susan says it really works!

Medicine Wagons and Tent Shows

Many new remedies and "cure ails" were

promoted by the early tent shows and medicine wagons that made their way

through the towns. They were very popular in the early 1900s and local people

would flock to the center of town to catch up on the latest "scientific

discovery" in the world of medicine.

Watkins and Baker offered all types of cough remedies and sold all kinds of spices and herbs.

Medicine shows were held in the Opera House and all kinds of liniments, patent medicines and even "hair growing" potions were offered!

At the Medicine Shows, coupons were given each time a person made a purchase. These coupons were saved, and the person with the most coupons won a special prize, such as watches or necklaces. Amanda Clausen remembers winning silverware at one time.

The Medicine Shows would stay in town as long as there was money coming in from the public. People recall them staying for as long as a week.

Around 1910, a Fish Wagon also came into Aspinwall and sold fresh fish. The owner spoke in High German, making it hard for people to understand him. He usually came around once a month.

ODDS AND ENDS

There was reportedly more cooking in the little shed

behind the blacksmith shop than fire for the forge ... It was something about

100 proof. The home brew was supposedly quite good; in fact, one gentleman who

hasn't visited town in quite a few years has hinted that he'll be checking

basements for bottles the next time he's here. "Haven't tasted anything

like it since," he has said. Unfortunately, the basement he particularly

wanted to check is no longer there...